Denmark – setting aside the previously described Jutland peninsula – is a nation of islands. Zealand is the biggest and by far most populated of them. Copenhagen is located on Zealand’s eastern shore, but some parts of the city — as well as the airport – lie on a different and much smaller island called Amager. Parts of it are urban, but in the west there is an area of reclaimed land called Kalvebod Fælled which is a nature reserve of flat wetlands and forests. The southern shore of Amager boasts beaches and quaint villages. And if this weren’t enough, there are even some (modest) hills.

For various reasons Amager has captured the imagination of Copenhageners. The Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen is nowadays mostly remembered for his brilliant fairy tales, but he published in a wide variety of genres. His first book was a fictional travelogue called A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager in the Years 1828 and 1829. The narrator of this book, who lives in central Copenhagen, on the last day of the year 1828 decides that he wants to become a writer. He thinks that walking to Amager will be helpful in this pursuit, and thus sets out on a nightly walk. Things soon take a fantastical turn and the narrator meets a colourful array of mythical figures, such as St Peter, Ahasverus, and even Death himself. Various enriching experiences are made. On one occasion the narrator gets hold of “100 Mile Støvler”, i.e. boots with which one can cover 100 miles in one step. While this sounds great in theory there are difficulties with the application. On his first attempt the narrator tries to walk to Norway, but misjudges the direction and his foot ends up at the bottom of the ocean. On the second attempt he tries to head south, but accidentally treads onto an elegant lady sitting in carriage in Austria. He thus gives up and sticks to Amager and his regular boots.

Not all associations Amager gives rise to are as poetic as those invoked by Andersen. During the latter’s time executions were still taking place on the island, and furthermore Copenhagen’s waste was delivered there, which gave rise to the nickname Lorteøen (shit island). Of more recent coinage is the term Amagernummerplade (Amager number plate), which denotes lower-back tattoos. On the culinary front there’s Amagermad (Amager food): a sandwich which – unlike the famous smørrebrød1The Muppet show contains a character who in the original is called the Swedish chef. In the German dub he is turned into a Danish chef, and his segments begin with a song whose lyrics are roughly “Smörrebröd, smörrebröd, römtömtömtöm”. – consists of two slices of bread with butter and fillings in between, and in particular two different kinds of bread: one slice is rugbrød (a dark Danish-style rye bread) whereas the other slice is white bread. Often the white bread is used as the bottom slice, and there are competing theories about why that is. One is religious: Consuming white bread was forbidden on Sundays, but God might not see it when hidden below the rest of the sandwich. The other theory has to do with the fact that for many centuries Amager had a substantial Dutch population. Supposedly the rye bread the Dutch produced was less solid than the Danish rugbrød and prone to crumble. The white bread thus had to serve as the base to ensure the integrity of the sandwich.

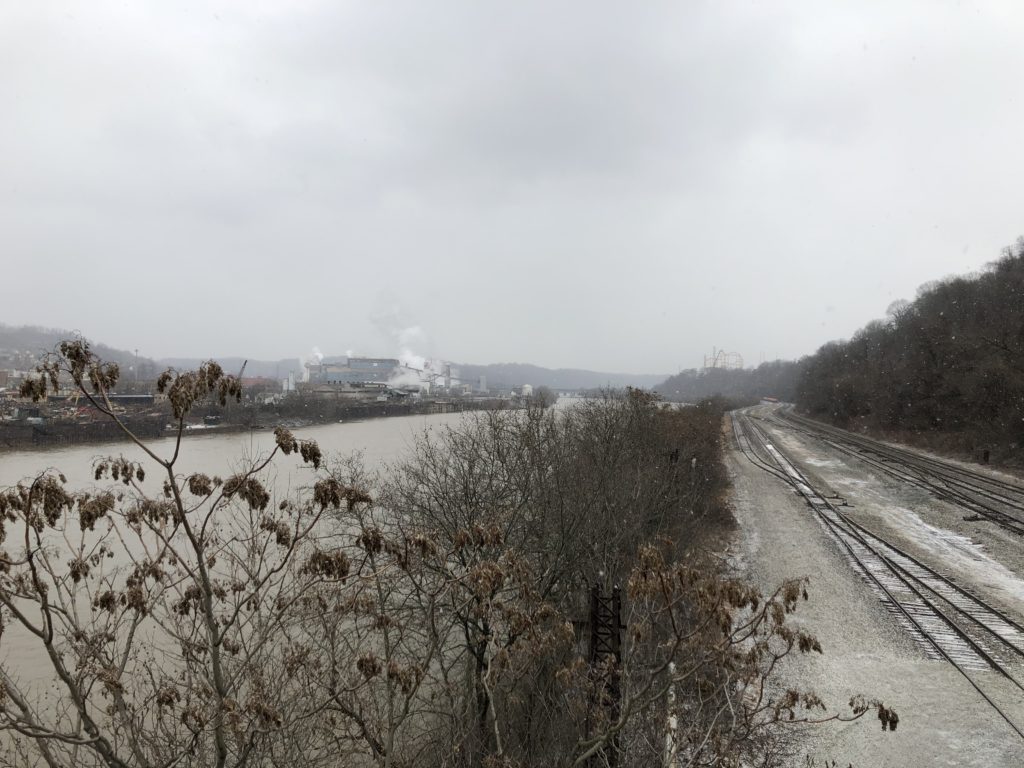

Nowadays one can explore Amager by walking the Amarminoen. This 27km walk begins in urban Amager next to the headquarter of Danish television (DR), then leads south through the nature reserves until hitting the coast, where the path turns east towards the village of Dragør. The scenery is varied and there is a nice mix of nature and urban elements like motorways and railway lines. As one comes closer to the airport one can also watch planes descend. Nordic noir fans might recognise some areas. In the first season of the popular Danish crime series The Killing (Forbrydelsen), the murder victim Nanna Birk Larsen is found dead in a river in the Pinseskoven forrest.

Since I am fan of coastal walks I especially liked the last few kilometres of the Amarminoen along the beach. During this section I enjoyed my sandwich on a bench with a view of the Øresund-bridge to Sweden in the distance.

Later, while walking past the village of Søvang, I came across a notice board announcing Denmark’s longest bathing bridge. The actual bridge was comically short, however, and certainly not 279m long as mentioned on the board:

Subsequent research solved this puzzle. Apart from the stump I saw, the actual bridge had been taken into storage for the winter, and was only scheduled to be reassembled a few days after my walk. In 1997 279 metres were sufficient to put the Søvang bridge into the Guinness Book of World Records, but since then a competitor has emerged. In 2014 a 320m long bathing bridge was opened in the northwest of Zealand.

Dragør, at the end of the Amarminoen, is a quaint village where the houses are yellow and have thatched roofs. I celebrated the completion of my walk with a coffee and a “soft ice“.

Some more reflections on H. C. Andersen’s journey are called for before concluding. The title of his book promised a walk to the easternmost point of Amager, but where exactly is that point? Comparisons of coordinates I have undertaken on Google Maps point towards a jetty in the Dragør harbour, but arguably that doesn’t really count since it is an artificial structure and probably wasn’t around in 1829 anyway. An area east of the airport, close to a maintenance shed by the Danish national railway, is a better fit. So did Andersen’s narrator go here? The text is not very specific. After entering Amager references to the external environment become sparse and generic. Fields and farms are briefly mentioned, and in the end the narrator is standing on a beach and contemplates what to do next while looking at the sea – which could happen pretty much anywhere.

There is a straightforward explanation for this lack of specificity. Scholars now agree that Andersen didn’t actually know Amager well when writing his book, and certainly hadn’t made it as far out as the easternmost point. He probably only knew the journey from central Copenhagen to Amagerport, which was one of Copenhagen’s four gates. This walk is also often recreated by contemporary explorers, but since it is only 3km it hardly fills the day. Despite not having met any mythical creatures I can warmly recommend to actually do the walk Andersen merely imagined.