I have long been interested in the state of New Jersey, which seems to be the Essex of America. Some years ago, on my first ever visit to the US, I flew into Newark Airport, and during the approach one of the flight attendants announced that people sitting on the left would now be able to see the Manhattan Skyline, whereas those sitting on the right could see the Garden State of New Jersey. I was sitting on the right, and what we saw were big roads, oil refineries, and container ports — just like in the intro to The Sopranos.

I was not putt off by this, and later even bought a book about the New Jersey Turnpike. But I only recently got the chance to actually spend some time in the state while visiting Princeton for two weeks. Princeton itself is pleasant enough but not very interesting, and so I was keen to go on some daytrips. Thankfully New Jersey has a relatively good network of commuter trains. The Princeton station is just off the main corridor that connects the big cities on the East Coast (DC-Philadelphia-NYC-Boston). A cute little shuttle service, called the Dinky, goes back and forth between the town and the main line. The ride just takes a few minutes.

On a sunny Saturday I headed towards the Dinky station in order to go to the famous Jersey Shore. While walking through the Princeton campus I encountered many students dressed up as Santa Claus. This turned out to be because of SantaCon: an annual tradition of going to New York to get drunk while looking like Santa. I was unfamiliar with this event, as I was with another tradition local to Princeton that I learned about in the novel The Rule of Four: the Nude Olympics. For several decades, on the first day of snowfall, second-year Princeton students would run around the campus naked at midnight. The university banned this rite of passage in 1999, however, because too many people got so drunk that they needed medical attention.

Thanks to the SantaCon crowd the train towards New York was so packed that I could barely squeeze in. But I was happy to count this as an authentic New Jersey experience — it is after all the most densely populated state in the US. I was the only passenger getting off at Rahway to change for the southbound North Jersey Coast Line service. I had decided to go to Asbury Park, since in addition to the Bruce Springsteen connection it was said to have a good boardwalk and a nice beach. I wasn’t disappointed.

After enjoying excellent coffee and a huge chocolate chip cookie on the boardwalk — which even had free wifi — I walked along the coast until the sun set. The only annoying part of of this trip was the journey back. While in general NJ Transit is quite fun to use, the train from the coast arrives at Rahway exactly 2 minutes after the southbound train on the Northeast Corridor has left, so that I needed to wait 58 minutes for my connection. I am not the only one who has spent more time in Rahway than they had hoped for though, since it is home to the East Jersey State Prison. In 1978 this prison became famous through the educational documentary Scared Straight. In it juvenile delinquents were sent to the prison so that inmates saving life sentences could shout at them (and everyone else around, such as the cameramen) about how terrible life in prison is. The documentary is narrated by Peter Falk, of Columbo-fame. Obviously the thought behind the screaming was that the juveniles would be put off by the experience and give up crime. But unfortunately subsequent studies suggest that the scare tactics actually led to an increase in crime.

Everyone agrees that going to New York is fun. It is less widely appreciated that one of the great things about approaching the city from the south are the excellent views of the New Jersey Meadowlands, a watery area of reeds and marshes just a few miles away from Manhattan. For many decades they were primarily used as dumping grounds for various kinds of garbage, including poisonous chemicals. But in more recent years they have been discovered as an exciting place to explore.

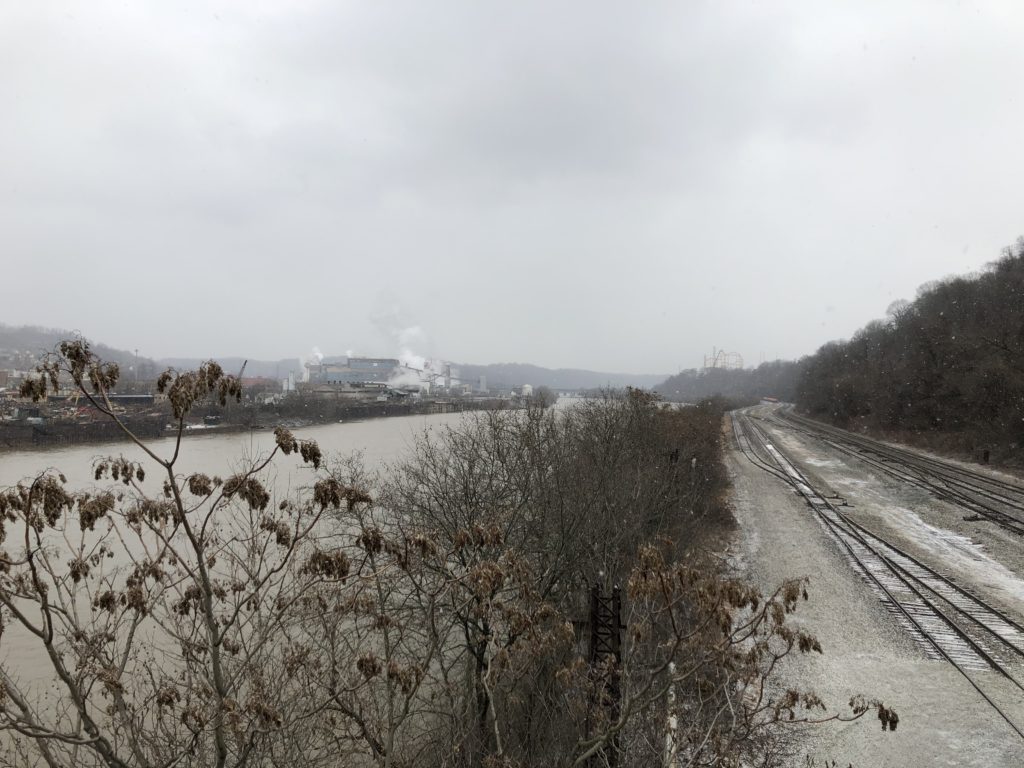

I had already noticed the Meadowlands a few years ago when taking the Amtrak from Pittsburgh to NYC. This time they made such a strong impression on me that I could think of little else after seeing them from the train again, and so I had to investigate whether it would be possible to visit them for a walk. Luckily the answer turned out to be yes, thanks to the Richard W. DeKorte Park which is accessible using trains and walking.

I thus had to go on another daytrip. On the previous day trains had been disrupted by a bull on the tracks at Newark station, but I didn’t have any problems and quickly arrived at Kingsland station in Lyndhurst.

Lyndhurst was very welcoming: there were several crossing guards making sure that the (few) pedestrians crossed the road safely. I was nevertheless a bit nervous about reaching DeKorte Park because I had to walk through the ominously named Disposal Road. People have disappeared in the Meadowlands before, and this name did not bode well. As a matter of fact the road wasn’t very scary at all, however, and it even had recently been renamed to honour a long-time member of the local fire department.

Walking through the Meadowlands turned out to be just as amazing as I had imagined it to be. Admittedly the air felt extremely salty, and the history of pollution made me wonder how healthy extended stays in this environment are. I nevertheless enjoyed my lunch — a hoagie from Wawa — on one of the benches provided. Later, while walking parallel to the western spur of the NJ Turnpike and after spotting an old car tyre in the water, I even saw someone fishing. It is not clear to me whether people actually eat Meadowlands fish though.

After having explored all corners of DeKorte park I headed back to the station for the train to Hoboken. I liked the grand railway terminal there and reflected on my adventure over a coffee. Then I enjoyed a more mainstream view of Manhattan. Who knows, maybe trips to the Meadowlands will become really popular among New Yorkers some day.

I needed to go to Newark to catch the train back to Princeton, and for the sake of variety I used the PATH to get there. A good choice, for as the sun was setting I got an excellent view of the Pulaski Skyway which runs parallel to the tracks. Once more New Jersey didn’t disappoint.